On Too-Bigness

An enduring problem of life.

The middle west is colloquially known as the Midwest. It includes a cluster of states (all of some, parts of others) that share certain cultural and geographic similarities. A critic might pejoratively describe the region as “sleepy” or “dull.” He might say its people are characterized by an obnoxious humility—the kind of folks who always have a preemptive apology loaded in the conversational chamber.

Should that critic keep going, he might call mediocrity the Midwest’s defining feature, joking that the “middle” in its name is appropriate given how middling it is. He may support this claim with the fact that, in the 1920s, sociologists Robert and Helen Lynd were looking to study a small city that was “not peculiar in any obvious way…the normal, average American small city,” and ended up choosing a Midwestern city called Muncie, Indiana.

At the time, cultural anthropology was in vogue. Western researchers would embed themselves in “primitive” cultures in Africa and the South Pacific, observing them as if they were distinct species. The Lynds embraced that ethnographic lens, decamping to Muncie for more than a year to immerse themselves in the collective life of the city.

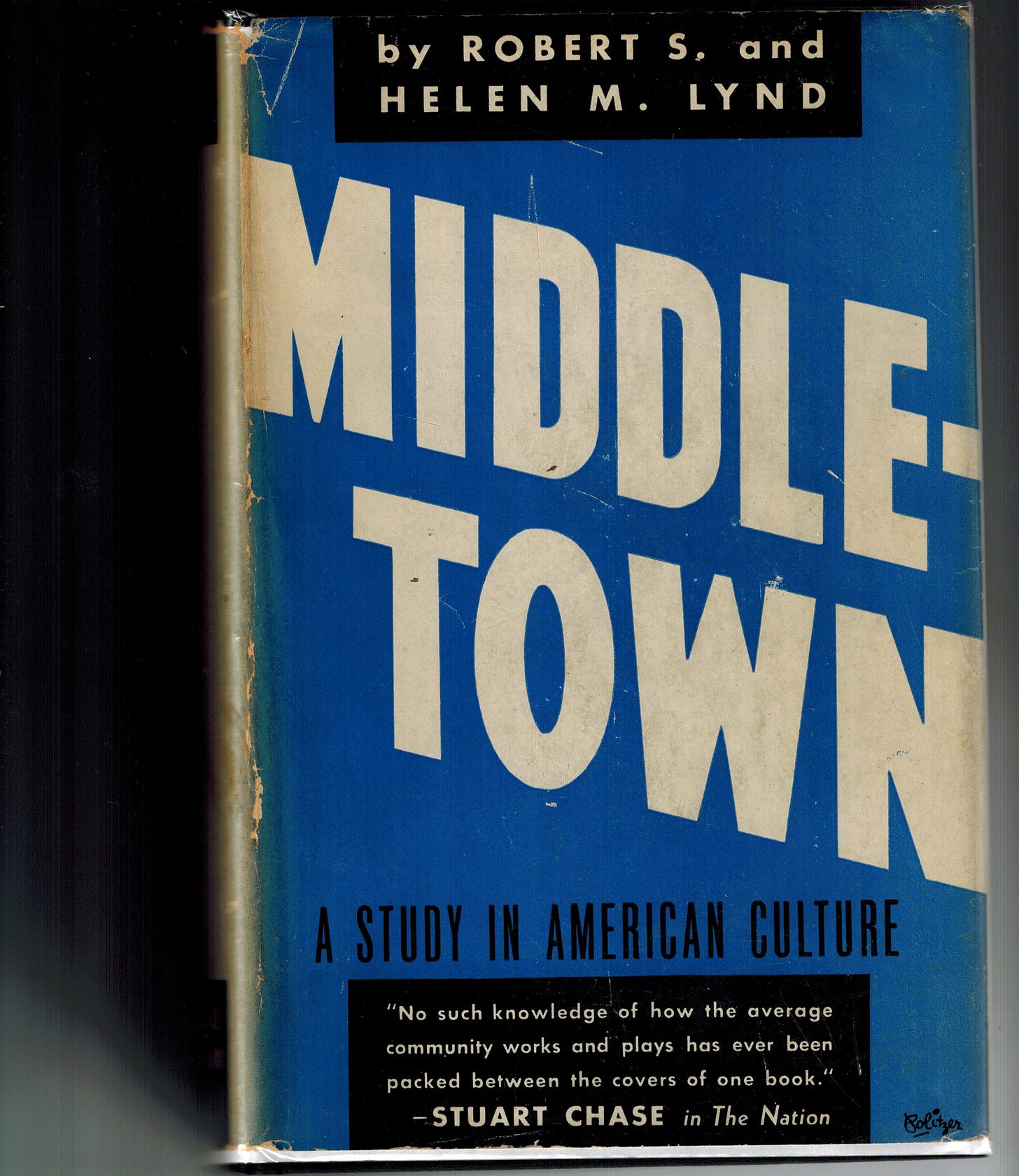

The result was a book called Middletown: A Study in Modern American Culture. It was a surprise commercial hit, selling tens of thousands of copies. Critics lauded it, comparing it favorably to Tocqueville’s Democracy in America for the way it captured the knobby contours of American life.

Having been born in Muncie 50 years after the Middletown study, I’ve always been curious about the book. But for years I steered clear of it, assuming the antiquated city it depicted would bear little resemblance to the one I grew up in. I also thought its academic framework would make for tedious reading.

A paradoxical thing happens as one ages. Things that seemed “old” in one’s youth stop feeling quite so far away. I eventually came to see that the interval between the Middletown study and my own life wasn’t so vast. In fact, the technological and cultural trends that shaped my childhood—mass media, the automobile, a sharp decline in religious observance—first took root in the 1920s.

So I read the book, and I now see why it struck such a chord with readers of the 1920s.

To attend closely to something for a very long time requires care. Like other ethnographers of the early 20th century—Mead, Hurston—the Lynds balanced academic reserve with human compassion. Native Midwesterners themselves (Robert was from southern Indiana; Helen, from Illinois), they no doubt saw shades of themselves in the people of Muncie. This helps explain the subtle note of tenderness that echoes throughout the text.

Middletown is broken up into six sections that, together, comprise all of the activities that constituted a life in 1924: Getting a Living, Making a Home, Training the Young, Using Leisure, Engaging in Religious Practices, and Engaging in Community Activities. Despite the bland descriptions, each section’s contents are deeply engaging, and occasionally poetic. One particularly moving passage has been lodged in my brain for days:

In addition to their various pursuits concerned with the immediacies of life about them, Middletown people engage in another activity, religious observance, whereby they seek to understand and to cope with the too-bigness of life.

The Lynds don’t elaborate on their charmingly awkward coinage, “too-bigness.” But the implication is that, for the residents of Muncie in 1924, life on its own terms was simply too much.

The people in Middletown were the first generation to live in a fully industrialized world—a condition that understandably triggered a feeling of psychic dislocation. The church offered a salve. But, as the Lynds reported, people were turning away from it, drawn from their pews to mesmerizing new attractions: the automobile, the cinema, the radio. It’s hard to say whether these innovations were a contributing factor to, or an alternative cure for, life’s too-bigness.

The traditions and rituals that had defined life for the people of Muncie were being replaced or rendered obsolete. One unfortunate casualty was the practice of group singing, which had been a hallmark of society in the 1800s. With the arrival of the radio and phonograph, people stopped singing themselves and started listening to others sing through machines.

If this sounds eerily similar to today, you’re catching on to the theme that grabbed me as I read Middletown. In the 1920s, new technologies were shrinking the world (the automobile) and encouraging passive receptivity (the radio, the cinema) instead of active creativity. People were rejecting church and other social gatherings for “motoring” and the movie house. Parents feared the corrosive effects of the latter, yet felt powerless as their children fell under its spell.

The current moment is like a cracked mirror image of the Middletown era. Just as machines replaced craftsmen then, AI threatens to replace knowledge workers today. The fear and helplessness that we felt during the COVID pandemic afflicted them during the Spanish flu outbreak. They had global instability; we have creeping authoritarianism.

Then as now, people fretted over the destabilizing effects of new technology even as they were sucked into its orbit. And today’s technology is so thoroughly godlike that we can hold the whole world in our hands. Who needs eternal salvation in the age of the infinite scroll?

Just like the people of Middletown, we live in strange, incomprehensible times. They sought to outrun confusion in a car; to cure alienation by staring at a big screen. Our methods of escape are direct descendants of theirs. Yet the too-bigness described by the Lynds in 1924 continues to cast a shadow over our lives. The marvel of Middletown isn’t that it transports the reader to a different era. It’s that it reveals the illusory nature of the divide between then and now.

Love this, especially "the too-bigness of life."